The Green New Deal resounds a political and systemic response to the twin crisis of climate change and inequality. With both the climate and economic crisis, governments have prioritized the interests of those who caused the problem, despite the consequences for working people.[1] To save the biosphere and the economy for working Americans, we must have massive public investment in clean, renewable energy, infrastructure, jobs and social services. This makes the Green New Deal an urgent and necessary step. I maintain that these investments must include the arts, especially the performing arts.

We need the arts to create new visions for society, but we also need the arts to bring people together to communally participate in new visions. Since 2016 classical pianist Hunter Noack has for three summers toured rural areas of Oregon with a 9-ft Steinway grand piano on a trailer, combining his love for music and the outdoors. His outdoor concerts collaborate with public lands agencies, as well as private property owners. Like much of America, Oregon typifies the urban-rural divides. Yet, at a concert in Fort Rock State Park southeast of Bend, local ranchers listened on horseback alongside outdoors enthusiasts, music buffs, and families from around the state. These concerts are presented free or at low cost. A third of his audience has never been to a classical concert before, let alone hearing the same piano you would hear in Carnegie Hall, and all of this in a stunning natural amphitheater. But that’s the point. Music brings people together and takes us to distant places. Creating a space for people of diverse political, ethnic, and class backgrounds to appreciate the land, as well as experience the arts together, is democratizing, inspiring, and desperately needed.

This is not a new idea. Noack’s In a Landscape: Classical Music in the Wild project was directly inspired by the Works Progress Administration, the Depression-era public works program which put millions of Americans back to work constructing buildings, roads, bridges, the thousands of trails in our National Parks and much more. The Federal Music, Theater, and Writer’s Projects included in the government stimulus package funded thousands of performances presented free to the public and many in parks. FMP programs raised musical standards in America, championed American composers and musicians, funded music teachers for poor families, supported amateur community ensembles, and funded folk song collection. Many of our nations most enduring and respected ensembles were created during the New Deal. And many more people had access to the arts and education and opportunities to enjoy the wonders of the land in which we live. People also spent time with each other. These arts programs created a community of Americans organized around shared values and a mission to restore America.

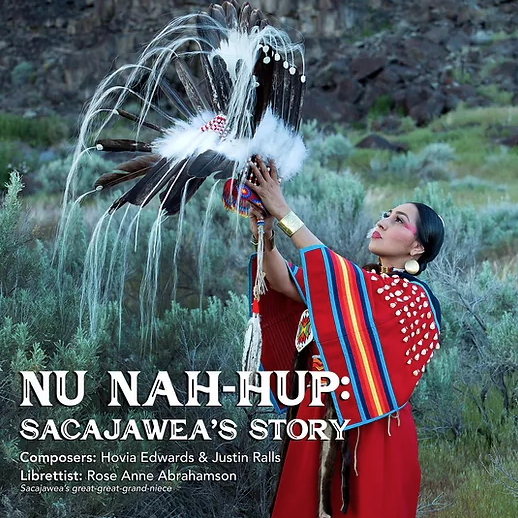

The National Endowment for the Arts in 2016 sponsored an initiative, ‘Imagine Your Parks,’ celebrating the centennial of the National Park Service, funding commissions, concerts and events across the country to great success. One such project, led by the Britt Festival in southern Oregon, commissioned composer Michael Gordon to compose a piece engaging Crater Lake National Park. A large orchestra and chorus premiered the piece at the rim of Crater Lake, collaborating with Steiger Butte Singers and Drummers, local members of the indigenous Klamath Tribes. The Federal Music Project similarly supported diverse ensembles, collaborations, and the nation’s folk, classical, jazz, and indigenous music. Especially in the West, ethnic and grassroots music thrived. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration explicitly encouraged folk song and vernacular music as a means of mending conflicts between racial, regional, and class groups in the country. These programs also brought classical music to a wider, diverse audience, and encouraged the creation of American works in the repertoire. Such previously marginalized music rose to unprecedented popularity.

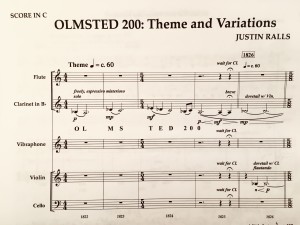

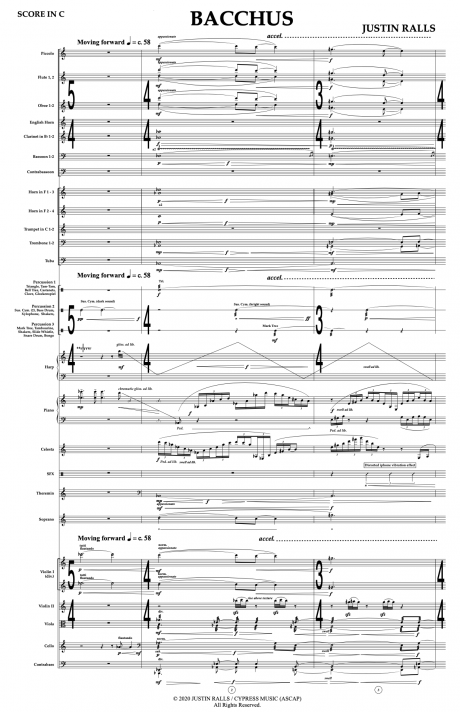

Programs which support cultural vibrancy, community, and appreciation of the land are a model which should be adapted and championed across the country in innovative ways, employing thousands of musicians, composers, artists, and writers to create, teach, and engage the public — supporting the values of equality and ecological responsibility. Green infrastructure projects could also include artist in residence programs and further opportunities for collaborations between diverse artists, communities, and environments. The city of Seattle established an artist residency for the historic Fremont Bridge in an ‘ongoing exploration of how to integrate art in cityscapes.’ Water Music NY was mounted by the Albany Symphony to musically explore the Eerie Canal. Washington State Department of Transportation has championed the first artist-in-residence for a statewide agency in the country. However, commissions and residencies for writers, musicians, and visual artists are often few and far between. There are far more talented, qualified artists than available opportunities. And these few opportunities often pay little more than a stipend. There is much great work being done by musicians and artists around the country, despite lack of funding and support. Many genres, including folk, jazz, classical, and ethnic musics are increasingly marginalized. Arts and music are habitually and deliberately cut from budgets. Yet there is a need, successful historical precedent, and community of artists and organizations ready, willing, and able to do their part to serve their nation and the planet. As in the Depression, they could use a little help from the government. I believe this is the spirit of the Green New Deal.

The arts have the potential to socially bond our communities around shared values and visions of what we may become, and this is what the Green New Deal should aspire to deliver. The U.S. Senate recently passed the decade’s largest public lands package, winning rare bi-partisan support. The overwhelming majority of Americans support public lands. Why? Because there are public lands in every district in America. The arts could help cultivate this truly silent majority into a dominant cultural force. Imagine the potential of numerous concerts, public art projects, community classes and events, environmental initiatives working in tandem with building renewable energy and infrastructure, ecological and public lands restoration and more. Environmental catastrophes, rising inequality and social anomie have created an existential emergency. We need spaces where we can commune with each other and the land, free from media grifting and electronic hallucinations. If we fail to imagine new ways of interacting with each other, the economy, and the resources we use and depend upon, then the struggle for a just and ecologically sound world recedes into fantasy.[2] We do not need more fantasy; we’ve had enough of that. We need active imagination.

[1] Jeffrey, Suzanne. “Up Against the Clock: Climate, Social Movements and Marxism,” ISJ Issue 148 http://isj.org.uk/up-against-the-clock/ ISJ 148 (Winter 2015).

[2] Magdoff, F., Williams, Chris, & Foster, John Bellamy. (2017). Creating an ecological society: Toward a revolutionary transformation. New York: Monthly Review Press. Pg. 18.