Field Notes from the Forest

Imagination, Goddard wrote, “is neither the language of nature nor the language of man, but both at once, the medium of communion between the two—as if the birds, unable to understand the speech of man, and man, unable to understand the songs of birds, yet longing to communicate, were to agree on a tongue made up of sounds they both could comprehend—the voice of running water perhaps or the wind in the trees. Imagination is the elemental speech in all senses, the first and the last, of primitive man and of the poets.”

This past spring I had the opportunity of staying as an Artist-in-Residence at the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, in the Cascade Mountains of Oregon. Founded in 1948, it is the most studied forest in the world. Sponsored by the National Forest Service, Oregon State University along with copious grants. The goal in the Andrews forest is both complex and utterly simple: study the forest ecosystem over time, and use this knowledge to inform our relationship with the forest. This mandate has illuminated vast scientific insights and controversial ideas of policy and purpose. The Andrews forest is home to some of the last remaining old growth forest in the world (500-800 year old trees), inspiring long-term studies and programs as a result. One such program is the Long Term Ecological Reflections (LTER), an international project documenting how ‘humans and the forest change over time.’ The LTER project in the Andrews forest is scheduled to last 200 years, from 2003-2203.

Over eons of floods, fires, storms, earthquakes, asteroids, our ‘apocalyptic planet’ is constantly reborn. Trees in an old growth forest in some ways never die, spending half their existence as slowly rotting logs. More trees grow from nurse logs, and giant moss covered, earthen virescent masses, neither moss nor earth nor tree, crisscrossing the forest floor below towering, leaning giants. Here the ancestors are not in the sky but among the living. These are nature’s epic poems, they are what scientists call ‘biologic legacies.’

Over eons of floods, fires, storms, earthquakes, asteroids, our ‘apocalyptic planet’ is constantly reborn. Trees in an old growth forest in some ways never die, spending half their existence as slowly rotting logs. More trees grow from nurse logs, and giant moss covered, earthen virescent masses, neither moss nor earth nor tree, crisscrossing the forest floor below towering, leaning giants. Here the ancestors are not in the sky but among the living. These are nature’s epic poems, they are what scientists call ‘biologic legacies.’

In the forest nothing is truly separate. Nutrients are stored in trees for a while and then slowly disperse to other organisms, other trees. In the old growth forest we find a metaphor for our own relationships; art itself is a receptacle of experiences and relations passed down over generations. The indigenous peoples of the Northwest sacrificed a tree, and carved into that tree animals stacked on top of one another; a clear metaphor for the ecological relationships inherent in the culture of the forest. Art and nature combine to tell a communal story. The tree gladly changes form to totem pole, such a tree is an honorable ambassador between human culture and the natural world.

To many cultures the owl is a totem of revelation and wisdom, of death and rebirth. The owl sees things others can’t and decides the fates of other creatures, whose power helps shape the forest.

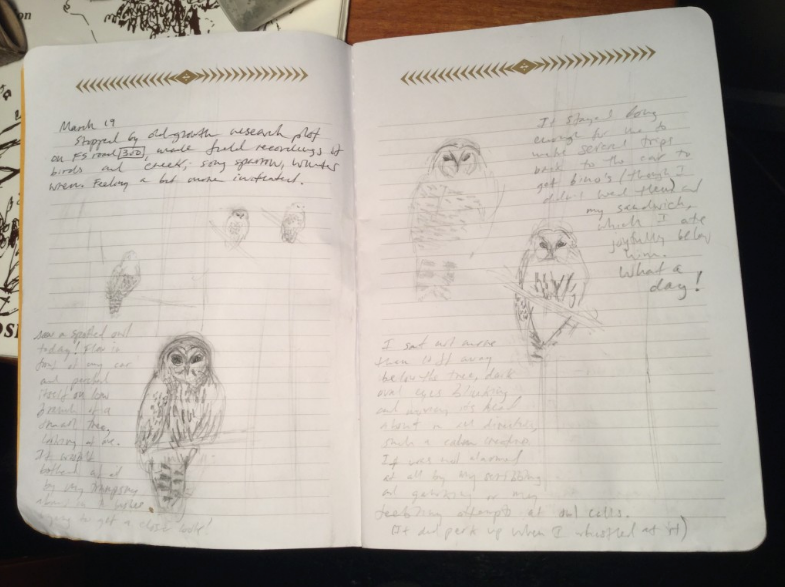

While I was driving, exploring the dusty forest service roads, a phantom bird swooped across the road, nearly over my windshield. It struck me as odd how my startling him made me take notice. If he had not made himself visible, I would have taken him as just so much scenery in the branches.

For nearly half an hour I sat no more than 10 feet below him, making sketches, recordings, and even eating my lunch. At the time, I couldn’t tell if it was a barred or spotted owl (the scientist in me said it was probably a barred, but the artist in me insisted I was being given a rare interview with the spotted owl). After returning to Andrews headquarters, the forest director, Mark Schulze, confirmed my sighting was a barred. Though, he said both owl species were ‘super tame’ and were relaxed around researchers of the forest.

The barred owl has steadily migrated from the Northeast over the years. Larger and more aggressive than the spotted, it directly competes for food and habitat. With higher reproducing rates, the barred often wins out. The lynchpin of the endangered species act and the fight for old growth forest, the spotted owl may lose out from under our nose by none other than nature herself. The reasons for this change are not entirely clear; fire suppression over the years has left forests open for barred owls to travel, climate change could also be a culprit. Researchers theorize the owls may have spread with the establishment of agriculture across the midwest, as farms created more suitable and adaptable habitat. It can be a heated discussion, whether the owls naturally migrated if humans helped them. I wonder about the impacts of these changes as we renegotiate our relationship with the forest and our sense of what is ‘human’ and ‘natural.’

My experience in the Andrews taught me one thing: we do not manage the forest, the forest manages us. It does not depend on us, but we do depend upon the forest for our air, our water, and our economic vitality. This is a lesson that resounds with many conversations I’ve had with indigenous people and conservationists. If, or when, the spotted owl is replaced by its brawnier cousin, what will this mean for the existing relationships in the forest? How will these changes change us? What is being gained or lost in these changes? What is there that we cannot yet see?

Without communion with the spotted owl, even if that communion is a fleeting glimpse, a periphery flash upon the eyes, or an invisible relationship, connected through myriad other processes, we will not know what it means to be fully human in the forest: to live with the elemental myths and dreams of nature.

As one meanders, shapes and faces of the forest appear. In Japanese folklore, this may be called a kodama or ‘tree spirit.’ Indeed, I walked right past this tree, only to feel something (or someone) was looking at me, I turned around and took the photo below. On the surface a kodama appears like an ordinary tree, but if one cuts it down one would become cursed.