Song of the Most Beautiful Bird of the Forest

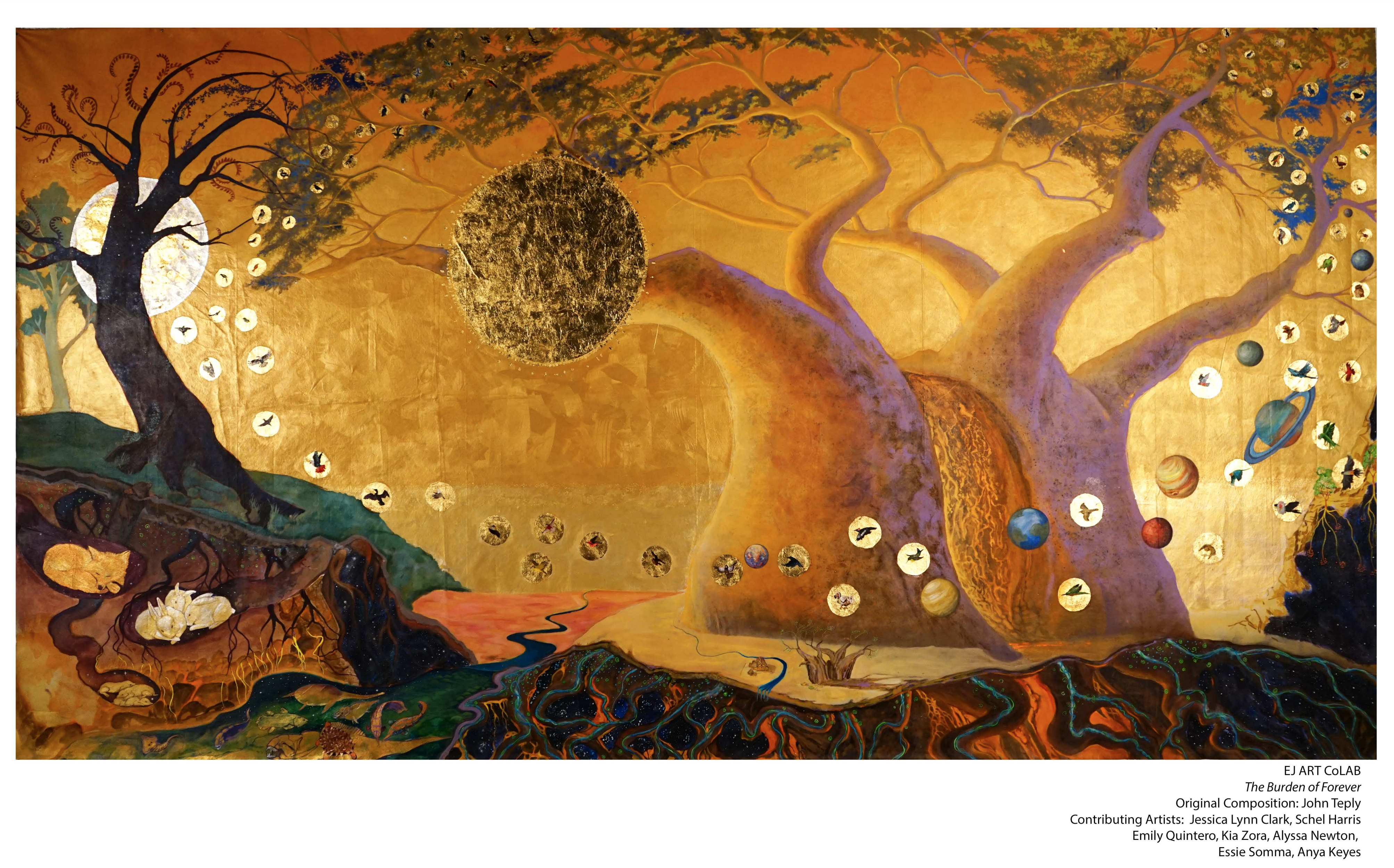

Above: 2020 painting, “The Burden of Forever,” inspired by the themes and story of SMBBF. Photo courtesy of John Teply and the Elisabeth Jones Art Center for Ecology and Social Justice.

Below are the prefatory pages to my Ph.D. dissertation, “Song of the Most Beautiful Bird of the Forest, an Eco-fairytale Opera in three Acts.”

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION COMPOSER’S NOTE:

The story of Song of the Most Beautiful Bird of the Forest is derived from a legend from the Mbuti people (also known as Bambuti), one of many ethnic groups of indigenous Central African Foragers of the Congo region of Africa. First published in Colin Turnbull’s classic ethnography, The Forest People, the legend tells of a young boy who upon hearing a bird brings it back to his camp. He asks his father to feed the bird (which his father reluctantly does) and the bird sings the ‘Most Beautiful Song in the Forest.’ This scene repeats three times, whereupon after the son leaves, the annoyed father kills the bird, and with the bird its song, and with the song the father unwittingly kills himself and drops dead.* The popular writer of comparative mythology, Joseph Campbell, interpreted this story as an allegory for what happens when a culture forgets its myths, stories, and life-supporting relationships. At a time when both the diversity of life on earth, as well as the cultural integrity and diversity of ethnic groups (such as the Mbuti) are severely threatened, I believe this story signifies a powerful lesson: if we do not respect, listen, and live in a balanced ecological relationship with the planet and with each other, we risk our own extinction. It also signifies that by diminishing the natural world, we diminish our own potential.

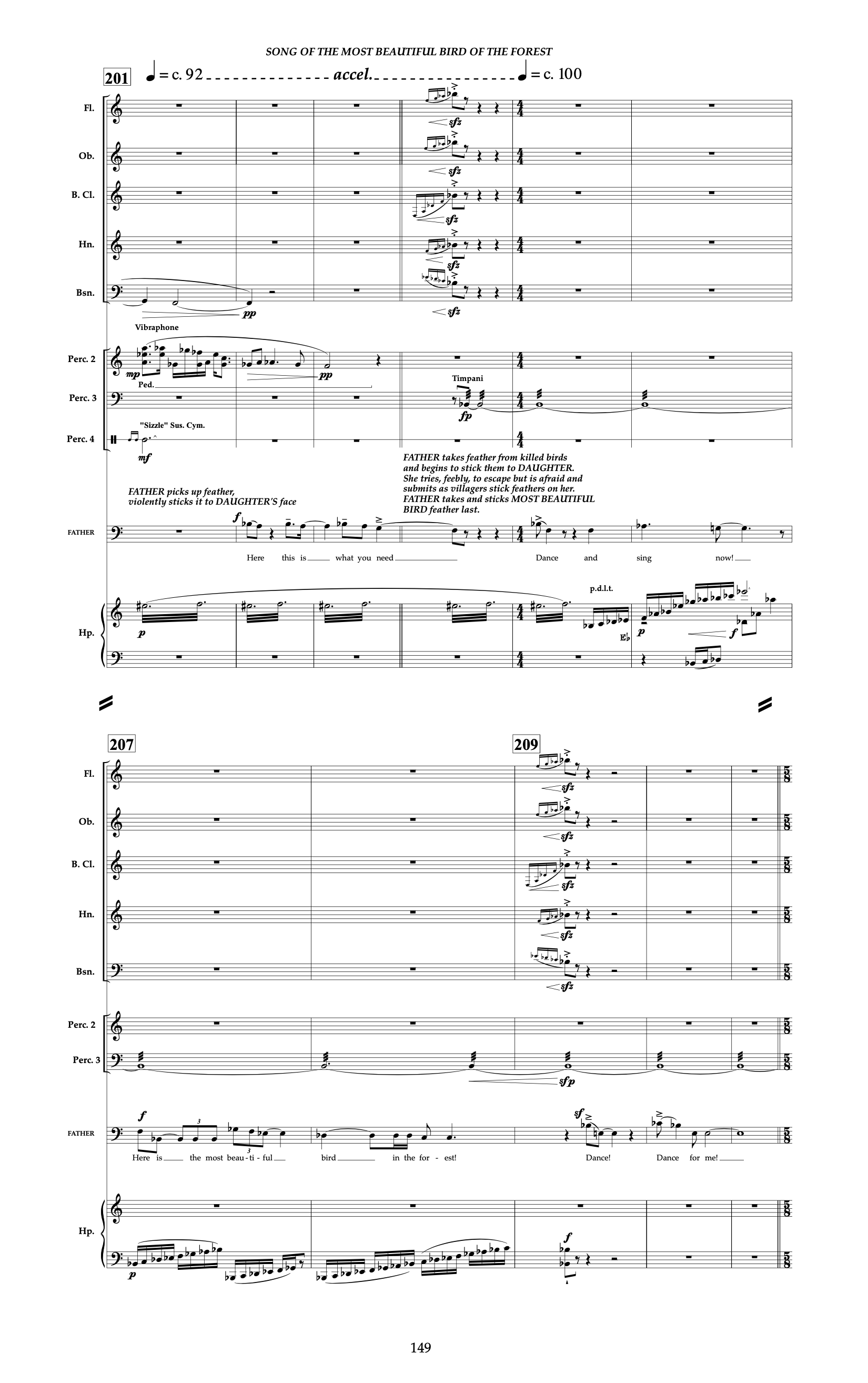

In adapting this story as a contemporary opera, I was sensitive to issues of cultural appropriation. I strove toward an emic perspective; hopefully creating a work that explores and honors the original meaning of the legend in a new form. I do not claim to represent, mimic, or take elements of Mbuti culture but rather explore function and the nature of relationships between music, story, and the natural world. Influenced by stories and folklore in creating an original composite story, I changed the character of the boy to a young girl and added additional characters (such as an older female mentor or shaman figure, She Who Sings from the Heart, and an otherworldly human-animal hybrid, Owl Spirit) as well as ecological themes (the bird’s song “brings the rain”). Most significantly, I explore an alternate ending: the young girl, after learning the song of the most beautiful bird, appears to sing the bird and the world back to life. The Daughter’s eventual learning of the bird’s magical song furthers the opera as a ‘coming-of-age’ story, where the Daughter discovers ecological awareness alongside her own empowerment. This adaptation took influence from many tales incorporating mythical birds, the power of song and dance to revitalize the world, and the corruptions of ignorance and power. Such influences include the fairy tale and Stravinsky opera, Song of the Nightingale, the Native American Blackfoot tale, The Buffalo’s Wife, Rimsky Korsakov’s The Snow Maiden, and Shakespeare’s King Lear among several others. The additional characters and their function also took influence from a Native American play, Power Pipes, by Spiderwoman Theater; a work that weaves themes of matrilineal indigenous knowledge, dance, storytelling, and song to heal trauma and initiate.†

In adapting this story as a contemporary opera, I was sensitive to issues of cultural appropriation. I strove toward an emic perspective; hopefully creating a work that explores and honors the original meaning of the legend in a new form. I do not claim to represent, mimic, or take elements of Mbuti culture but rather explore function and the nature of relationships between music, story, and the natural world. Influenced by stories and folklore in creating an original composite story, I changed the character of the boy to a young girl and added additional characters (such as an older female mentor or shaman figure, She Who Sings from the Heart, and an otherworldly human-animal hybrid, Owl Spirit) as well as ecological themes (the bird’s song “brings the rain”). Most significantly, I explore an alternate ending: the young girl, after learning the song of the most beautiful bird, appears to sing the bird and the world back to life. The Daughter’s eventual learning of the bird’s magical song furthers the opera as a ‘coming-of-age’ story, where the Daughter discovers ecological awareness alongside her own empowerment. This adaptation took influence from many tales incorporating mythical birds, the power of song and dance to revitalize the world, and the corruptions of ignorance and power. Such influences include the fairy tale and Stravinsky opera, Song of the Nightingale, the Native American Blackfoot tale, The Buffalo’s Wife, Rimsky Korsakov’s The Snow Maiden, and Shakespeare’s King Lear among several others. The additional characters and their function also took influence from a Native American play, Power Pipes, by Spiderwoman Theater; a work that weaves themes of matrilineal indigenous knowledge, dance, storytelling, and song to heal trauma and initiate.†

The character of the Owl Spirit is my personal interpretation of a being that mediates between worlds. I purposely did not take direct influence from any specific culture, and acknowledge the cultural diversity of Owl beings throughout the world, including the diversity of Native American interpretations of the Owl. Rather, it is my own ecological and mythological Owl as an other-than-human ambassador—a being between night and day, and for the animals it eats, between life and death—which I find compelling and relevant to my own experience in the forest of the Pacific Northwest. Such a mediator between worlds, bringing messages from beyond human experience, is the Owl Spirit’s function in the opera, guiding the daughter and audience in a liminal space, a place of transformation. It is possible to interpret Owl Spirit as trans-gender—a group that I hold no claim to represent— yet, whose presence may deepen the significance of this character in the liminal space of the opera. On many levels the opera embraces a liminal quality of processing and living within transition. As the Earth’s climate and biosphere transitions into new and unknown states, so perhaps a hybrid being, neither human nor animal, male nor female, material nor spiritual, could perhaps uniquely guide us in new mythologies of transformation.

While the music of the Mbuti is extraordinary (included in the UNESCO Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage) the opera is not set in Africa and the music (with the exception of the two ensemble dances) is not overtly African. The opera could be set in any forest community in the world, real or imagined. Rather, I strove to ask deeper questions of how non-Western traditions and cultures functioned in their environment and how music can sonically explore these questions. For example, Mbuti music is performed outdoors in the rainforest, comingling with the natural soundscape; both human and animal sounds take advantage of the acoustic environment in an orchestration of human and non-human sound and expression, co-evolved over time. Their traditional stories, dances, and rituals engage real and symbolic beings and elements of the forest, making explicit links between culture, environment, and performance. Engaging these links through contemporary Western opera and my own unique perspective in time and place was a driving force in conceiving Song of the Most Beautiful Bird of the Forest.

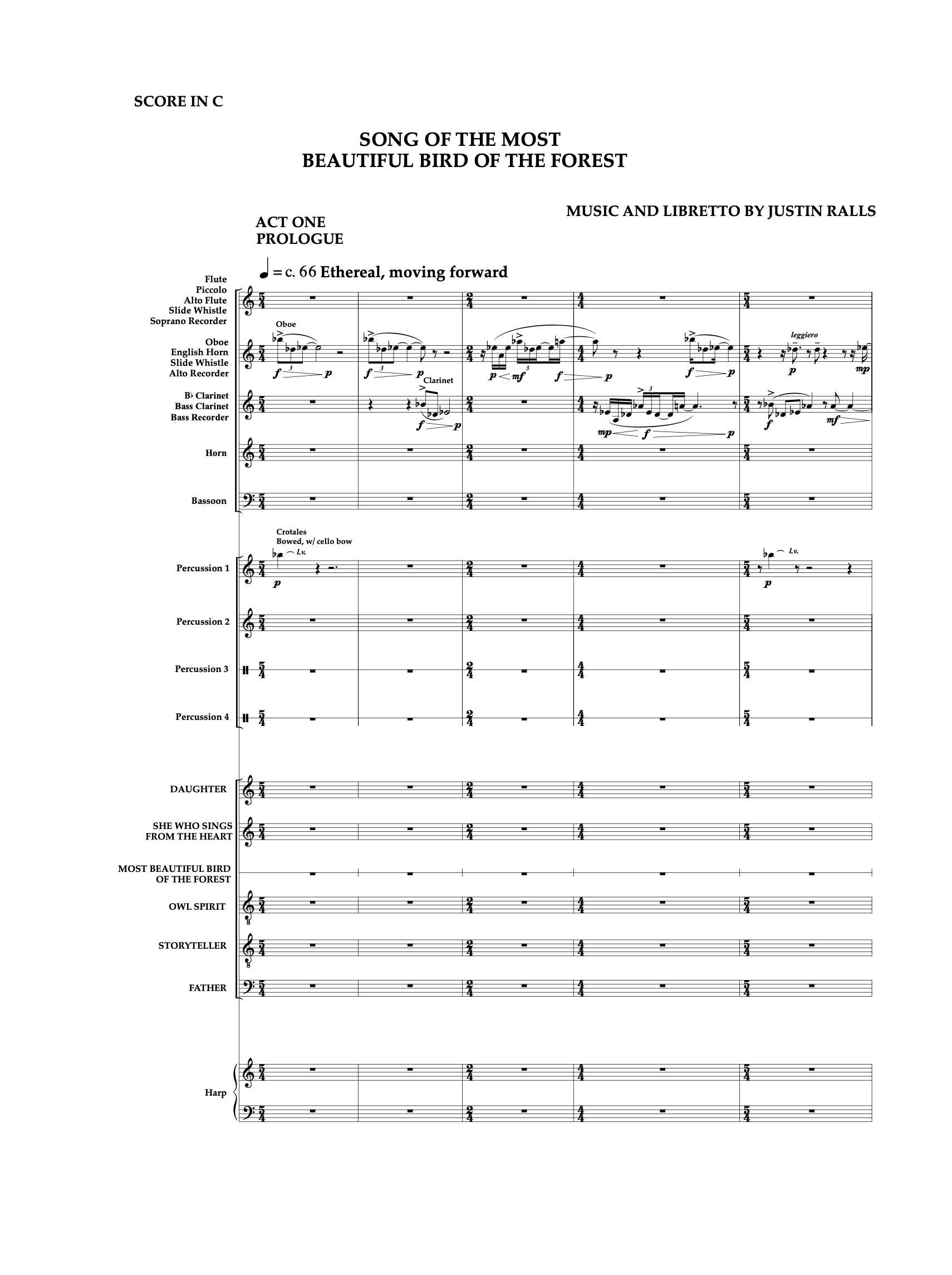

While it is not required, I encourage the outdoor performance of this piece in a natural forest amphitheater. In this way, the opera may further mythologize and engage many environments, forests, and cultures on their own terms. Potential outdoor performance influenced the opera’s instrumentation of percussion, winds, and harp—all instruments that carry well outdoors (e.g. mm. 1-29, Prologue, Act One). The idea of ‘acoustic niche’ is explored in novel improvisatory episodes, where winds (doubling on slide whistles and bird callers) may freely create their own soundscape (mm. 87-113, Prologue, Act One). In another example (m. 595, Act Two), the Daughter and instrumentalists may freely improvise, interact, and mimic each other in an imagined soundscape. This approach, I believe, explores the functions and aesthetics of world traditions without appropriating specific cultural characteristics. The combination of voice, winds, and percussion instruments also have a rich legacy of evoking nature and ritual in composed music from the last century from Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring to the West African- inspired minimalist work of Steve Reich, the atmospheric music of George Crumb, and the outdoor operas and site-specific works of Canadian composer R. Murray Schafer’s Patria (whose work has been influenced by the function and beliefs of First Nations traditions, without appropriating cultural meanings). In the case of these influences, I strove to learn from other templates of musical expression and context that could explore the opera’s themes in novel ways and open cultural exchange and new modes of expression.

For example, the “war dance” at the close of, Scene One, Act One (m. 337) is loosely derived from the Ghanaian Ewe dance Agbekor, which I learned while studying with Ghanaian master drummer and dancer, Dr. Habib Iddrisu. Scholar Jeff Todd Titon has written that the origin of Agbekor may derive from hunters watching monkeys (alluded to in a story told by the Father in Act One, Scene One). Like many African dances, it has evolved from a culturally specific ritual into a pan-cultural performance practice, staged in ever-evolving variations. My variant of Agbekor portrays a dance of war between the people and animals. In this way, I have striven to preserve the cultural origins of this Ewe dance, employing its meaning in the context of the opera and its themes of conflict and relations between humans and animals. This is further explored in the opening dance of Act Three. This dance is a transcription of Balankung, a traditional dance of the Dagomba ethnic group of Northern Ghana. According to Dr. Habib Iddrisu, this dance was heard in his childhood to scare away animals and birds away from crops at harvest time. This dance, however, is no longer performed in Ghana. Dr. Iddrisu has revived it as a presentational performance work with his group, Dema, at the University of Oregon (with whom I learned and performed the piece). The original dance included slit log drums (“balankung”) alongside gourd shakers and ankle rattles worn by dancers. Dr. Iddrisu made an addition of the cajón (an Afro-Caribbean instrument) as homage to the ongoing evolution of West African music across the globe. In this spirit, the dance is included in the score (with permission) in an effort to further preserve this unique cultural tradition and contribute to this ongoing evolution. As with Agbekor, the inclusion of Balankung exemplifies an emic perspective where unique cultural context is woven into the story—not to represent Africa or the Dabomba people—but as exploration of internal function (and the Father again articulates the dance’s function within the story-world of the opera; mm. 148-150, Scene One, Act One). My hope is the opera synthesizes disparate influences, filtered through a unique artistic voice. Balankung also reveals questions of the complexity of human/animal relations, especially in the context of agricultural society. The relationships between different societies and their local fauna and the other-than-human world are always in flux. The inclusion of Balankung ventures into its own liminal space, opening up questions of cultural appropriation vs. cultural exchange in new expression. I believe such exchange is necessary if cultures are to come together, learn, listen and create paradigms for new and emerging futures. We must work together in concert toward a newly defined respect for each other and the planet, highlighting our diversity but also our common goal toward a more compassionate ecological society. In this way the opera is an experiment in such exchange, initiating a challenging but necessary conversation, as we work toward redefining our personal and societal relationship with the natural world and relations between culture vis-à-vis another.

For example, the “war dance” at the close of, Scene One, Act One (m. 337) is loosely derived from the Ghanaian Ewe dance Agbekor, which I learned while studying with Ghanaian master drummer and dancer, Dr. Habib Iddrisu. Scholar Jeff Todd Titon has written that the origin of Agbekor may derive from hunters watching monkeys (alluded to in a story told by the Father in Act One, Scene One). Like many African dances, it has evolved from a culturally specific ritual into a pan-cultural performance practice, staged in ever-evolving variations. My variant of Agbekor portrays a dance of war between the people and animals. In this way, I have striven to preserve the cultural origins of this Ewe dance, employing its meaning in the context of the opera and its themes of conflict and relations between humans and animals. This is further explored in the opening dance of Act Three. This dance is a transcription of Balankung, a traditional dance of the Dagomba ethnic group of Northern Ghana. According to Dr. Habib Iddrisu, this dance was heard in his childhood to scare away animals and birds away from crops at harvest time. This dance, however, is no longer performed in Ghana. Dr. Iddrisu has revived it as a presentational performance work with his group, Dema, at the University of Oregon (with whom I learned and performed the piece). The original dance included slit log drums (“balankung”) alongside gourd shakers and ankle rattles worn by dancers. Dr. Iddrisu made an addition of the cajón (an Afro-Caribbean instrument) as homage to the ongoing evolution of West African music across the globe. In this spirit, the dance is included in the score (with permission) in an effort to further preserve this unique cultural tradition and contribute to this ongoing evolution. As with Agbekor, the inclusion of Balankung exemplifies an emic perspective where unique cultural context is woven into the story—not to represent Africa or the Dabomba people—but as exploration of internal function (and the Father again articulates the dance’s function within the story-world of the opera; mm. 148-150, Scene One, Act One). My hope is the opera synthesizes disparate influences, filtered through a unique artistic voice. Balankung also reveals questions of the complexity of human/animal relations, especially in the context of agricultural society. The relationships between different societies and their local fauna and the other-than-human world are always in flux. The inclusion of Balankung ventures into its own liminal space, opening up questions of cultural appropriation vs. cultural exchange in new expression. I believe such exchange is necessary if cultures are to come together, learn, listen and create paradigms for new and emerging futures. We must work together in concert toward a newly defined respect for each other and the planet, highlighting our diversity but also our common goal toward a more compassionate ecological society. In this way the opera is an experiment in such exchange, initiating a challenging but necessary conversation, as we work toward redefining our personal and societal relationship with the natural world and relations between culture vis-à-vis another.

An emic perspective of cultural exchange applies to the musical evocation and engagement of nature as well. The opening motive (heard in the winds, mm. 1-6, Prologue) is a musical transcription of the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō bird (Moho braccatus), an extinct member of the Australo-Pacific honeyeaters endemic to the island of Kaua’i. While the opera is influenced by acoustic ecology and natural soundscapes generally, this one species in particular deserves special recognition as its song (and its intrinsic musical motives) permeates the entire piece both on an episodic as well as structural and symbolic level. Not only is the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō’s flute-like, hallow, song incredibly haunting (the recording I listened to may have been the last male bird singing to a mate which would never come), but I felt the bird’s island forest environment was symbolic of ‘Island Earth’ and the ‘glocal forest’ (a local environ linked to global ecologies). Indeed, the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō represents the ‘Song of the Most Beautiful Bird’, whose motives interject the drama and which is eventually learned and sung by the Daughter. Lastly, the inclusion of the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō’s song asks questions of romanticizing nature, the Daughter’s song without a doubt is romantic in character, however this music changes with the inclusion of the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō motive which acts to segue into an arguably more primordial texture, evoking the rainforest soundscape of the prologue. The closing soundscape and inclusion of bird song also reveals that throughout the opera we have heard the song of the most beautiful bird all along, even if we didn’t know it. This is especially apt in the midst of the climate crisis and Earth’s sixth mass extinction.

An emic perspective of cultural exchange applies to the musical evocation and engagement of nature as well. The opening motive (heard in the winds, mm. 1-6, Prologue) is a musical transcription of the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō bird (Moho braccatus), an extinct member of the Australo-Pacific honeyeaters endemic to the island of Kaua’i. While the opera is influenced by acoustic ecology and natural soundscapes generally, this one species in particular deserves special recognition as its song (and its intrinsic musical motives) permeates the entire piece both on an episodic as well as structural and symbolic level. Not only is the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō’s flute-like, hallow, song incredibly haunting (the recording I listened to may have been the last male bird singing to a mate which would never come), but I felt the bird’s island forest environment was symbolic of ‘Island Earth’ and the ‘glocal forest’ (a local environ linked to global ecologies). Indeed, the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō represents the ‘Song of the Most Beautiful Bird’, whose motives interject the drama and which is eventually learned and sung by the Daughter. Lastly, the inclusion of the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō’s song asks questions of romanticizing nature, the Daughter’s song without a doubt is romantic in character, however this music changes with the inclusion of the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō motive which acts to segue into an arguably more primordial texture, evoking the rainforest soundscape of the prologue. The closing soundscape and inclusion of bird song also reveals that throughout the opera we have heard the song of the most beautiful bird all along, even if we didn’t know it. This is especially apt in the midst of the climate crisis and Earth’s sixth mass extinction.

The theme of extinction is made explicit when the Daughter meets Owl Spirit, who, in the words of She Who Sings From the Heart, “guides us between worlds.” Owl Spirit’s favorite meal, “flying-squirrels,” reveals this mysterious character to perhaps be a Northern Spotted Owl, an iconic and controversial species of Northwest old- growth forests that, despite our best efforts, is on its way toward extinction. As the branches of the tree of life are broken, Owl Spirit confronts the young girl with a terrible question, “You do not know who will go next do you?” The last scene of the opera—when the young girl appears to sing the bird back to life—is intended to be ambiguous, dependent upon the interpretation of the artists realizing the work and the perspectives of the audience receiving it. My hope is the presence of the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō engages the central themes and questions of the opera: can we learn the Song of the Most Beautiful Bird of the Forest and prevent our own extinction?

*Turnbull, Colin M. The Forest People. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1962. Print. Clarion Book. Pg. 82-83.

† D’Aponte, Mimi, and Theatre Communications Group, Publisher. Seventh Generation: An Anthology of Native American Plays. First ed. New York: Theatre Communications Group, 1999. Pg. 155-195. ‡ Todd Titon, Jeffrey, Editor. Worlds Of Music: An Introduction to the Music of the World’s Peoples. New York: Schirmer Books, 2002. Pg. 73. 3